Alcohol is a significant component of the human diet, with both risks and benefits depending on the amount consumed. Excessive alcohol intake is responsible for a large number of deaths and costs billions of dollars in the United States alone. It is the leading cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality and can cause other health issues such as hypertension, stroke, and gastrointestinal cancers.

On the other hand, low to moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. The current guidelines suggest that men should consume no more than two alcoholic drinks per day, and women no more than one.

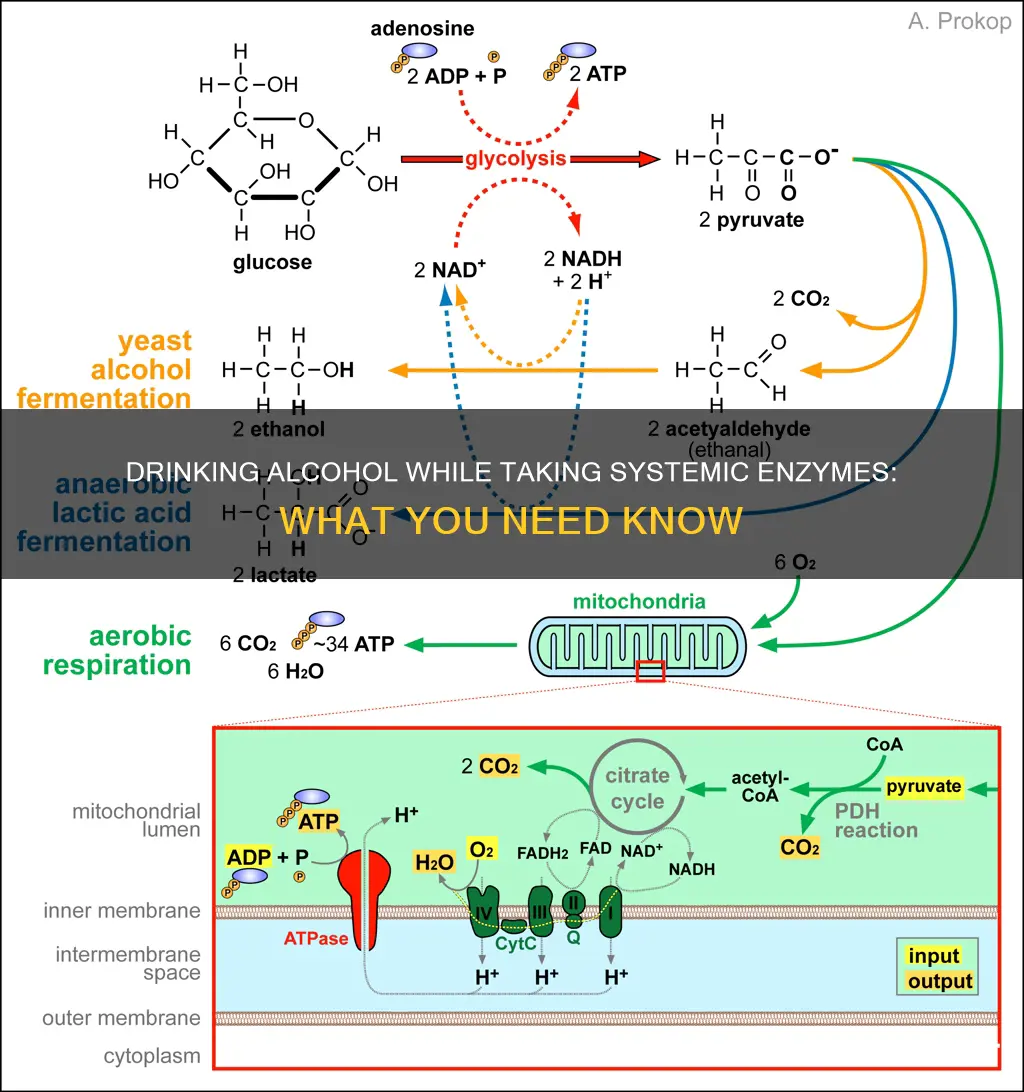

The body breaks down alcohol through enzymes, specifically alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). This process starts in the stomach, where ADH can detoxify about one drink per hour. The alcohol is first converted into acetaldehyde and then into acetate, which can be easily processed by the body.

Research on alcohol consumption primarily focuses on addiction, but some companies are working on solutions to limit the side effects of drinking, such as hangovers. These include stimulating alcohol by-product degradation through probiotics or enzymes.

Systemic enzymes are those that act on substances that have been absorbed into the bloodstream, and they are typically used to reduce inflammation and improve overall health. While there is no direct research on the effects of combining systemic enzymes with alcohol, it is known that alcohol consumption can change how efficiently the body breaks down foods and toxins, which could potentially interfere with the action of systemic enzymes. Therefore, it is advisable to consult a healthcare professional before combining the two.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Alcohol's effect on the body | Alcohol can disrupt the microbiome by killing healthy gut bacteria, irritate the gut, speed up the digestive system, and cause intestinal inflammation. |

| Alcohol's effect on enzymes | Alcohol can change how efficiently the body breaks down food and toxins, and can affect the liver. |

| Systemic enzymes | Can help heal and rebuild the intestinal lining. |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) | An enzyme that breaks down alcohol into acetaldehyde, and then into acetate, so it can be processed by the body. |

| Beer and wine | Beer and wine contain alcohol, which has both risks and benefits for the body. |

What You'll Learn

Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) enzymes

Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) is a group of dehydrogenase enzymes that are found in many organisms, including humans. In humans, ADH breaks down alcohols that are otherwise toxic and also helps generate useful byproducts during the biosynthesis of various metabolites.

In humans, there are seven genes that encode the different classes of ADH enzymes. These genes are all located on chromosome 4. The enzymes produced from these genes are slightly different in their activities and are classified as class I through V based on their enzymatic properties and sequence similarities.

The main function of ADH is to catalyse the oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde, a highly reactive and toxic byproduct. This is achieved through a redox reaction involving the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+).

The ADH1B gene, in particular, has several functional variants. One variant involves a SNP that leads to either a histidine or an arginine residue at position 47 in the mature polypeptide. The histidine variant of this enzyme is much more effective at converting ethanol to acetaldehyde. However, the enzyme responsible for converting acetaldehyde to acetate remains unaffected, leading to a buildup of toxic acetaldehyde, which can cause cell damage.

Studies have shown that variations in ADH that influence ethanol metabolism can impact the risk of alcohol dependence. Certain variants of the ADH1B gene, which increase the rate of ethanol conversion to acetaldehyde, have been found to be protective against alcohol dependence, especially in Asian populations.

In summary, alcohol dehydrogenase plays a crucial role in the metabolism of ethanol and has important implications for human health and alcohol consumption.

Beer and Sore Throats: Is It Safe to Drink?

You may want to see also

How alcohol affects the gut

Alcohol can have a detrimental effect on the gut, causing inflammation and disrupting the balance of bacteria in the gut microbiome. The gut microbiome is made up of bacteria, viruses, and fungi, and is essential for supporting the immune system, metabolism, and regulating inflammation.

When we drink alcohol, it affects the oral microbiome and the digestive system, as well as other organs. Here are some of the ways in which alcohol can impact the gut microbiome:

- Alcohol can change the composition of the gut microbiome, causing an imbalance known as dysbiosis, which can lead to intestinal inflammation.

- Alcohol and its metabolites can be toxic and harm the microbiome. The gut microbiome creates metabolites when breaking down alcohol, and these can be harmful.

- Alcohol can cause a leaky gut, where the protective mucus layer on the intestinal lining is eaten away, allowing toxins to enter the bloodstream.

- Alcohol can cause gastritis, overwhelming the enzymes in the stomach lining and causing vomiting and diarrhea.

- Alcohol can lead to an overgrowth of bacteria in the gut, which can increase the release of endotoxins and promote inflammation.

- Alcohol can disrupt the intestinal barrier, increasing its permeability and allowing pathogens and harmful substances to enter the bloodstream.

- Alcohol can affect mucosal immunity, decreasing the innate immune response and making the body more susceptible to intestinal pathogens.

- Alcohol can suppress the activity of Paneth cells, which are one of the intestine's main lines of defense against bacteria, leading to bacterial overgrowth and endotoxins entering the intestinal barrier.

Overall, alcohol consumption can have a range of negative effects on the gut, including increasing intestinal permeability, disrupting the balance of bacteria, and causing inflammation. These effects can have broader consequences for overall health, including an increased risk of liver disease, neurological disease, gastrointestinal cancers, and inflammatory bowel syndrome.

Florida Driving: Beers and Legal Boundaries

You may want to see also

Alcohol and liver enzymes

Alcoholic liver disease covers a spectrum of disorders, from fatty liver to alcoholic hepatitis and, ultimately, alcoholic cirrhosis. The liver is particularly susceptible to alcohol-related injury because it is the primary site of alcohol metabolism. As the liver breaks down alcohol, it produces by-products such as acetaldehyde and highly reactive molecules called free radicals, which are toxic to the body.

The liver has a considerable capacity for regeneration, so symptoms of liver damage may not appear until the organ is extensively damaged. Epidemiological studies suggest that a threshold dose of alcohol must be consumed for serious liver injury to occur. This threshold is higher for men than for women.

The mechanisms that influence liver injury are complex and not yet fully understood. Oxygen-related factors, inflammation, and fibrosis all play a role in alcohol-induced liver damage. In addition, genetic variations in enzymes that metabolise alcohol and influence liver injury risk have been identified.

Not all alcoholics develop serious liver disease, and this is thought to be due to a combination of genetic, environmental, and dietary factors.

Liver damage caused by alcohol consumption can be detected through various biomarkers, including serum gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activities, as well as ferritin and albumin protein concentrations. These biomarkers can be elevated even in individuals without apparent liver disease, indicating early-stage liver damage.

Treatment for alcoholic liver disease depends on the extent of the disease and includes medical treatment, nutritional support, and, in severe cases, liver transplantation.

Beer and the Sabbath: A Religious Perspective

You may want to see also

The body's response to alcohol

Alcohol affects everyone, but how it affects you depends on a range of factors, including your health, age, body composition, and genetics. Here is how alcohol affects the body:

Short-term effects

The short-term effects of drinking too much alcohol can include interpersonal conflict, risky or violent behaviour, hangovers, alcohol poisoning, falls, accidents, lowered inhibitions, and risky behaviours. The severity of these effects depends on how much a person drinks, their body's ability to metabolise alcohol, hydration, and food consumption. Alcohol poisoning is a life-threatening emergency and requires immediate medical attention.

Long-term effects

Long-term alcohol consumption contributes to more than 200 different types of diseases and injuries. Some of the most common alcohol-related long-term harms include:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Cancers, including of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, oesophagus, liver, colorectum, and female breast

- Nutrition-related conditions, such as folate deficiency and malnutrition

- Overweight and obesity

- Mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression

- Alcohol tolerance, dependence, or addiction

- Long-term cognitive impairment

- Self-harm and suicide

Effects on specific body systems

Brain

Alcohol interferes with the brain's communication pathways and can affect the way the brain looks and works. These disruptions can change mood and behaviour and impair judgement and coordination.

Heart

Drinking a lot of alcohol over a long time or too much on a single occasion can damage the heart, leading to cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, and high blood pressure.

Liver

Heavy drinking takes a toll on the liver and can lead to various problems and inflammations, including steatosis or fatty liver.

Pancreas

Alcohol causes the pancreas to produce toxic substances that can lead to pancreatitis, a dangerous inflammation that causes swelling, pain, and impaired function.

Immune system

Drinking too much can weaken the immune system, making the body more susceptible to diseases like pneumonia and tuberculosis. Even up to 24 hours after getting drunk, the body's ability to ward off infections is slowed down.

Non-Alcoholic Beer: Sobriety Friend or Foe?

You may want to see also

The effects of moderate alcohol consumption

Alcohol is a simple molecule called ethanol, which affects the body in many ways. It directly influences the stomach, brain, heart, gallbladder, and liver. It affects levels of lipids (cholesterol and triglycerides) and insulin in the blood, as well as inflammation and coagulation. It also alters mood, concentration, and coordination.

The terms "moderate" and "a drink" are used loosely and fuel the debate about alcohol's impact on health. In the US, one drink is usually considered to be 12 ounces of beer, five ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of spirits. Each delivers about 12 to 14 grams of alcohol on average, but there is a wider range now that microbrews and wine are being produced with higher alcohol content.

The latest consensus places moderate drinking at no more than one to two drinks a day for men and no more than one drink a day for women. This definition is widely used in the US.

Heavy drinking can cause inflammation of the liver (alcoholic hepatitis) and lead to scarring of the liver (cirrhosis), a potentially fatal disease. It can increase blood pressure and damage heart muscle (cardiomyopathy). Heavy alcohol use has also been linked to several cancers, including mouth, pharynx, larynx, oesophagus, breast, liver, colon, and rectum.

Even moderate drinking carries some risks. Alcohol can disrupt sleep and impair judgment. It interacts dangerously with various medications, including acetaminophen, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, painkillers, and sedatives. It is also addictive, especially for people with a family history of alcoholism.

There may also be health benefits associated with moderate alcohol consumption. More than 100 prospective studies show an inverse association between light to moderate drinking and the risk of heart attack, ischemic stroke, peripheral vascular disease, sudden cardiac death, and death from all cardiovascular causes. The effect is fairly consistent, corresponding to a 25-40% reduction in risk.

The benefits of moderate drinking aren't limited to the heart. In the Nurses' Health Study, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, and other studies, gallstones and type 2 diabetes were less likely to occur in moderate drinkers than in non-drinkers.

In summary, moderate alcohol consumption can be defined as no more than one to two drinks per day for men and no more than one drink per day for women. While moderate drinking may offer some health benefits, such as a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, it also carries risks, including liver disease, high blood pressure, certain cancers, injury, impaired judgment, depression, anxiety, and addiction. The overall impact of alcohol depends on various factors, including genetics, lifestyle, and individual health status.

Beer and Mayvret: One Drink, Safe or Not?

You may want to see also