Alcohol is often associated with weight gain, but does drinking beer specifically slow down your metabolism? Well, it's a little more complicated than a simple yes or no answer. While alcohol itself is not proven to slow down metabolism, it does have other effects on the body that can impact weight management. For example, alcohol is treated as a toxin by the body, which prioritises removing it, potentially leading to a build-up of fat in the liver. Additionally, heavy drinking can damage the intestines, affecting the body's ability to absorb nutrients and potentially leading to malnutrition. Beer also tends to have more carbohydrates than other alcoholic drinks, which may contribute to abdominal obesity. However, studies have not shown a clear link between alcohol consumption and weight when looking at whole populations. In fact, very heavy drinking can be associated with lower body weight. So, while beer doesn't directly slow down metabolism, excessive consumption can have negative health consequences, including weight gain.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Effect on metabolism | Alcohol does not slow down metabolism but it is prioritised by the body over other nutrients, which can lead to a build-up of fat in the liver. |

| Calories | Beer contains 155 calories per 12 ounces. |

| Weight gain | Alcohol is associated with weight gain due to its calorie content and its effect on appetite. |

| Binge drinking | Men who binge drink are more likely to be obese and have high blood pressure, blood sugar and triglycerides. |

| Appetite | Alcohol can increase appetite and disrupt sleep patterns and metabolism, leading to weight gain. |

| Metabolism rate | Alcohol has a higher metabolic rate than food, meaning more calories are burnt processing it. |

What You'll Learn

Alcohol is treated as a toxin by the body

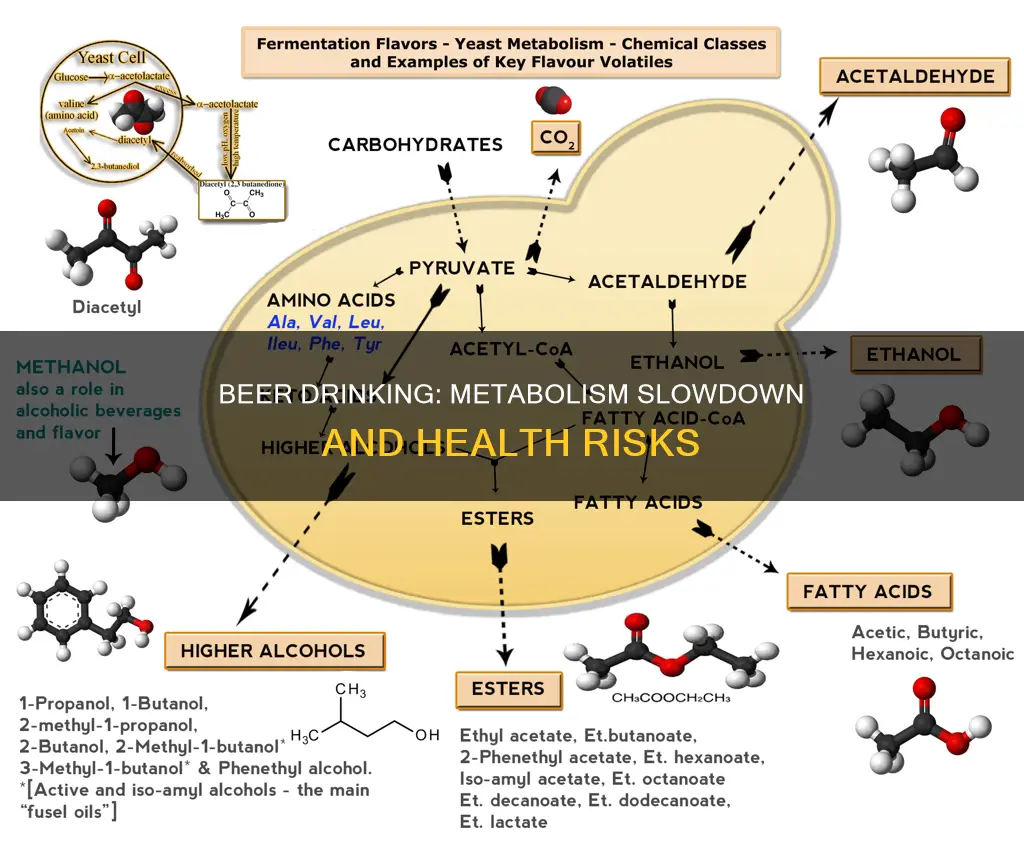

Alcohol is a toxin that the body works hard to eliminate. Within minutes of taking a sip, your fat metabolism can wane. Your body treats alcohol as a toxin, and removing it becomes the top priority. This means that your body will stop burning its stored carbs and fat for energy and will instead utilise the alcohol.

The liver does the majority of the hard work in processing alcohol and removing it from our system. However, about 10% of alcohol is also eliminated through our breath, sweat, and urine. Whatever is left in the body will slowly be eliminated over the next 7-12 hours following drinking. Although the liver does the hardest work in eliminating toxins, alcohol use impacts all the other major organs as well.

There are two toxins in alcohol that the body needs to work hard to eliminate: acetaldehyde and acetic acid. When your body breaks down ethanol, it produces a carcinogen called acetaldehyde that damages DNA. This molecule is needed by nearly every cell in our body for information on how to function, repair and regrow. If cells cannot properly repair themselves, cancer can grow.

Alcohol can also alter the body's oral and gut microbiome, which is described as the balance of bacteria, viruses and fungi that help to keep the body healthy. One of the microbiome's roles is to separate alcohol toxins so that the body can remove them. The gut microbiome is a critical link between the digestive system, the liver, and the immune system, playing a big part in how our body metabolises alcohol and manages the amount of ethanol or toxins that come from alcohol.

Beer and Dengue: Is It Safe to Drink?

You may want to see also

Alcohol has a higher metabolic rate than food

When you drink alcohol, your body puts all the other foods you've consumed on the back burner and devotes itself to metabolising the alcohol first. This is because, unlike carbs, protein and fat, your body doesn't have a storage capacity for alcohol. So when you drink, getting it out of your system becomes your body's immediate priority.

The average metabolic capacity to remove alcohol is about 170 to 240 grams per day for a person weighing 70 kilograms. This would be equivalent to an average metabolic rate of about 7 grams per hour, or about one drink per hour.

While alcohol may have a higher metabolic rate than food, it can still deter your fitness goals. Alcohol lowers your inhibitions and impairs your ability to make rational decisions. This can lead to poor food choices and a lack of motivation to exercise. Additionally, alcohol can disrupt your sleep patterns and mess with your appetite, both of which can contribute to weight gain.

It's important to note that drinking alcohol in moderation is generally considered safe for most people. Excessive alcohol consumption, on the other hand, can lead to health issues, including weight gain and an increased risk of preventable death.

The Magic Behind Beer Filtration: Using Sheet Filters

You may want to see also

Alcohol can increase appetite

Alcohol can have a significant impact on energy intake and appetite. While alcohol itself is calorie-dense, providing 7 kcal of energy per gram, it also increases energy intake by making people feel hungrier once they start eating. This is supported by studies where participants reported increased hunger ratings after ingesting alcohol and beginning to eat. However, alcohol does not seem to increase general hunger but rather stimulates appetite once eating has commenced.

Alcohol can also reduce the feeling of being satiated or full after a meal. This is due to its inhibitory effect on the secretion of leptin, a hormone responsible for inhibiting hunger and inducing feelings of fullness. Additionally, alcohol may cause weight gain by increasing appetite. A study found that women's brains responded more dramatically to the aromas of desirable foods after drinking, leading them to consume more of these foods.

The effect of alcohol on appetite and energy intake is complex and influenced by various factors, including drink choice, drink frequency, binge-drinking, sleep quality, dietary nutrition, and individual differences. For example, someone may associate red wine with good meals and, as a result, be predisposed to eat more when drinking it. On the other hand, they may associate champagne with New Year's Day hangovers and, therefore, be less inclined to eat. The carbonation in some drinks or the alcohol itself can also numb the mouth and dull the sense of taste, potentially impacting appetite.

Furthermore, the expectation of drinking alcohol can influence appetite. In a study where participants consumed alcohol-free beer or juice, their caloric intakes increased more after the beer, demonstrating the power of expectation and association when it comes to alcohol and appetite.

While alcohol may not directly slow down metabolism, its impact on appetite and energy intake can indirectly lead to weight gain if consumption is not carefully managed.

Beer and Kidney Health: Long-Term Drinking Effects

You may want to see also

Alcohol can disrupt sleep and appetite

Alcohol can negatively impact your sleep and appetite, which can lead to weight gain.

Alcohol is a sedative, and while it may help you fall asleep, it suppresses REM sleep, causing sleep fragmentation and nightmares. A study from the University of Michigan Alcohol Research Center found that heavy drinkers slept less than non-drinkers (43 minutes less per night) and that the sleep they did get was of inferior quality.

Sleep is critical to weight loss, and when we don't get enough of it, our energy system can misfire. We feel hungrier than we should, and we make poor diet choices. In a French study, people consumed 560 more calories during the day following a night of poor sleep than they did after sleeping eight hours.

Alcohol can also increase your appetite. A Purdue University study found that artificial sweeteners, like those in diet drinks, may disrupt the body's ability to count calories. When you eat or drink something sweet, it normally contains calories. But because diet drinks contain no calories, the body compensates by stimulating your appetite and causing you to feel hungry.

Alcohol can also lead to binge eating. It triggers a release of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which makes you feel good. fMRI scans of social drinkers show decreased activity in brain circuits involved in detecting threats, along with increased activity in circuits involved in reward. At the same time, your body releases ghrelin, an appetite-stimulating hormone, and galanin, a neuropeptide that may lead to eating more fat. This can result in hyperphagia, or an abnormally increased appetite.

While alcohol does not slow down metabolism, it can disrupt sleep and increase appetite, both of which can contribute to weight gain.

Accutane and Alcohol: Is Beer-Drinking Safe?

You may want to see also

Alcohol can be associated with lower body weight

Alcohol consumption has been linked to lower body weight in some studies, but the evidence is mixed and the relationship is complex. Here are four to six paragraphs exploring this topic in detail:

While some studies have found a positive association between alcohol consumption and body weight, particularly in men, the relationship is not straightforward. For example, a systematic review by the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE) found inconclusive results, with some studies showing positive, negative, or no association between alcohol and weight gain. Additionally, the present data does not provide clear evidence that beer intake is associated with general or abdominal obesity. However, when there is a positive association, it tends to be stronger for abdominal obesity (fat around the stomach) than for general obesity, and this association is more commonly found in men than in women.

Several factors influence the relationship between alcohol and body weight. Firstly, alcohol can inhibit fat burning and is high in kilojoules or calories. It can also increase hunger and cravings for salty and greasy foods. Secondly, drinking behaviour and patterns play a role. Frequent light or moderate drinking may have a protective effect, while heavy drinking is more consistently linked to weight gain. Binge drinking and drinking intensity (the amount consumed per drinking occasion) are also risk factors for weight gain. Thirdly, individual factors such as physical activity levels, sleeping habits, genetics, and other lifestyle choices can influence the association. For example, individuals who drink moderately may also have healthier lifestyle habits that protect them from weight gain. Finally, the type of alcoholic beverage may matter. Beer consumption, especially in excess of one pint per day, has been linked to abdominal obesity, possibly due to its higher carbohydrate content. Wine, on the other hand, may interfere with fat accumulation in fat cells and reduce their size, making it a better option for weight management.

The impact of alcohol on weight is further complicated by its effects on appetite and energy balance. Alcohol can stimulate food intake and influence hormones related to satiety, such as leptin and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). It can also affect central neurotransmitter systems, such as opioid, serotonergic, and GABAergic pathways, which may increase appetite. Additionally, alcohol may influence energy expenditure and thermogenesis, potentially counteracting its impact on weight gain. However, the net effect of these factors is not yet fully understood.

While the relationship between alcohol consumption and body weight is complex, heavy drinking and binge drinking have been more consistently associated with weight gain and obesity. This may be due to the additional calories from alcohol, the inhibition of fat burning, and the impact on appetite and energy balance. However, it is important to note that other factors, such as physical activity levels and overall lifestyle choices, also play a significant role. Therefore, while alcohol may be a contributing factor to weight gain, it is not the sole determinant, and individual variations exist.

In conclusion, while some studies suggest an association between alcohol consumption and lower body weight, particularly in men, the evidence is mixed and influenced by various factors. Heavy drinking and binge drinking are more consistently linked to weight gain, but individual variations and lifestyle choices also play a significant role. Therefore, moderation in drinking and adopting a healthy lifestyle are important to maintain a healthy weight.

Beers to Avoid: The Worst Brews You Shouldn't Try

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Drinking beer does not slow down your metabolism. However, since the body cannot store alcohol, it is quickly absorbed through the small intestines and ends up in the bloodstream, causing the body to prioritise metabolising alcohol over other nutrients. This can lead to a build-up of fat in the liver, which is one of the first steps towards liver disease.

Beer is considered a "liquid calorie" drink, meaning it can cause weight gain. Beer contains carbohydrates, which can contribute to abdominal obesity. A study found that men who binged drank, defined as consuming more than seven drinks per week, were more likely to have obesity and high blood pressure.

According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), moderate drinking is defined as up to two drinks per day for men and one drink per day for women. Exceeding this amount can increase the risk of weight gain and abdominal adiposity, commonly known as a beer belly.