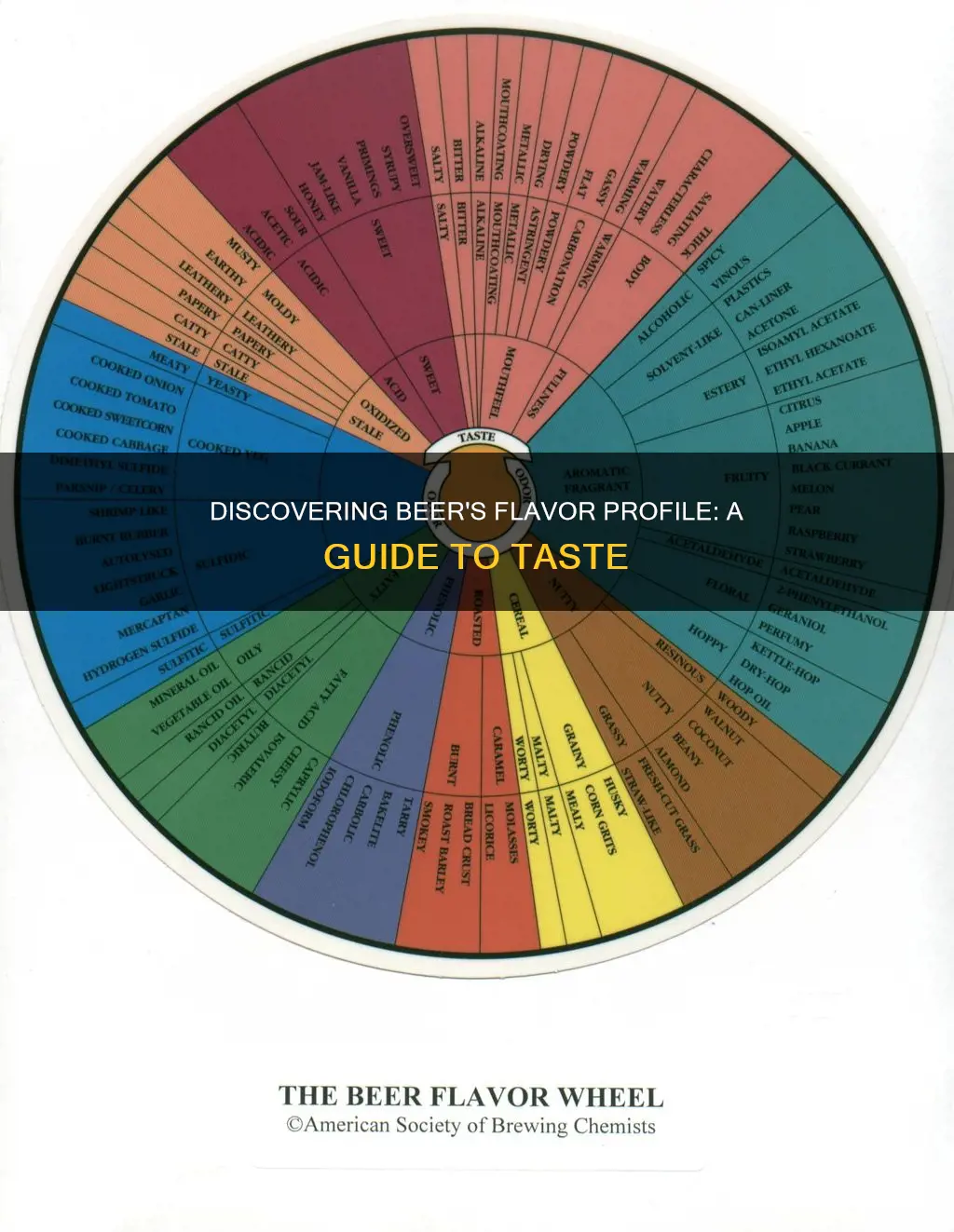

Beer is a complex beverage with a wide range of flavours, and identifying these flavours can be challenging. The flavour components of a beer are determined by its unique combination of carbonation, hops, malt, water, and yeast, as well as the varying aspects of the brewing process and the brewer's personal touches. The same flavours may be perceived differently by different people, but developing a descriptive vocabulary can help make the language of beer more accessible. Beer flavours can be broadly categorized into seven groups: crisp, hop, malt, roast, smoke, fruit and spice, and tart and funky. Each of these categories has numerous subcategories, with distinct flavour profiles achieved through different brewing techniques and ingredients.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Crispness and Refreshment | Crisp and refreshing beers tend to have low to moderate thickness or mouthfeel, with limited to mild levels of fruit flavours and bitterness. |

| Fruit Flavours | Fruit flavours can be delicate, such as green apple, berries or pear, or bold, like citrus or tropical fruit. |

| Bitterness | Bitterness in beer is largely due to the amount and type of hops used. Other factors include the malt profile and alcohol content. |

| Thickness or Mouthfeel | A beer's mouthfeel is influenced by the types of grain used in the malt, the yeast strain, and the level of carbonation. |

| Carbonation | Beers with higher levels of carbonation will feel lighter in texture and weight. |

| Aromas | Beers can have a variety of aromas, including spicy, herbal, and floral notes. |

| Colour | Beer colours range from straw to amber, yellow to brown, copper to dark brown, and pale gold to dark. |

| Unique Flavours | Off flavours can include dimethyl sulfide (boiled vegetables), acetaldehyde (wet grass), diacetyl (buttery popcorn), and ethyl acetate (nail polish remover). |

What You'll Learn

- Sweetness: derived from residual sugars, with notes of caramel, toffee, and chocolate

- Bitterness: the distinctive edge in beer, derived from hops

- Acidity: the tangy quality, similar to the tartness in wines

- Roastiness: a strong flavour from dark, roasted malts, with coffee-like, chocolatey, or smoky notes

- Hoppiness: the aromatic and bitter qualities of hops added during fermentation

Sweetness: derived from residual sugars, with notes of caramel, toffee, and chocolate

Sweetness in Beer

Sweetness in beer is derived primarily from residual sugars that remain after the fermentation process. These sugars are not consumed by the yeast during fermentation, and they contribute to the perception of sweetness on the palate. The type and amount of residual sugars present can vary depending on the beer style and the brewing process, leading to a range of sweet flavor profiles.

When tasting beer, you may detect notes of caramel, toffee, or chocolate, which contribute to the overall sweetness. These flavors are developed during the brewing process and can be accentuated by specific yeast strains and fermentation conditions. Caramel sweetness, for example, is often a result of using specialty malts that have been kilned or roasted to produce caramelized sugar flavors. The longer the malt is heated during this process, the darker the color and the more intense the caramel sweetness will be.

Toffee and chocolate flavors, on the other hand, are often derived from darker roasted malts, such as chocolate malt or black malt. These malts contribute complex flavors that can range from sweet toffee to bitter coffee or licorice notes. The roasting process breaks down the sugars in the malt and creates new flavor compounds, adding depth and complexity to the beer's sweetness.

The presence of certain fermentable sugars can also influence the perception of sweetness. For example, beers with a higher proportion of maltose, a sugar that is slower to ferment, may exhibit a fuller body and a slightly sweeter profile. Additionally, the use of adjunct sugars, such as lactose (milk sugar) or honey, can add distinct sweet flavors to the beer. These sugars are often non-fermentable by brewer's yeast, resulting in a residual sweetness that enhances the beer's overall character.

To detect and appreciate the sweetness in beer, it is important to pay attention to the aroma, flavor, and aftertaste. The aroma may provide hints of the sweet notes to come, while the flavor will give you a more comprehensive understanding of the beer's sweetness. The aftertaste, or finish, will reveal how the sweetness lingers or evolves, providing a lasting impression of the beer's character.

German Beer Imports: Different or Just Marketing?

You may want to see also

Bitterness: the distinctive edge in beer, derived from hops

Bitterness is a key element in beer that can either elevate a well-rounded beer or put drinkers off. It is primarily derived from hops, the flowers or cones of the humulus lupulus plant. While hops are added to beer for various reasons, including preservation and creating a "hoppy" aroma, they are essential for adding bitterness.

Sources of Bitterness in Beer

Although hops are the primary source of bitterness in beer, it's important to note that other ingredients can also contribute to bitterness. For example, fruits, herbs, and even vegetables added during brewing can impart bitterness. Some common bittering agents include orange zest, spruce tips, juniper, and certain types of malt.

Measuring Bitterness: IBU and Beyond

The bitterness of beer is often measured using International Bitterness Units (IBUs), which quantify the concentration of bittering compounds, mainly isomerized and oxidized alpha acids found in hops. However, IBUs don't tell the whole story, as they don't account for other bittering agents or individual differences in taste perception.

The human palate can generally detect bitterness up to a certain threshold, typically around 100 IBUs. Beyond this point, additional bitterness may not be noticeably different to most people.

Factors Affecting Bitterness Perception

The perception of bitterness in beer is influenced by various factors beyond just the presence of bittering compounds. The amount and type of hops added, the timing of their addition, and the specific hops variety can all impact the bitterness level. Additionally, the presence of malt can balance out bitterness, with higher malt content leading to a less bitter-tasting beer.

Other factors, such as water composition (specifically the sulfate-to-chloride ratio), yeast attenuation, and the use of spices, can also affect the perceived bitterness of a beer.

Bitterness in Different Beer Styles

Different styles of beer will have varying levels of bitterness, catering to a range of taste preferences. For example, India Pale Ales (IPAs) are known for their high bitterness levels, typically ranging from 40 to 100 IBUs or more. On the other hand, wheat beers and lagers tend to have lower IBU values, usually falling between 10 and 20 IBUs.

Understanding the sources and nuances of bitterness in beer can enhance your appreciation of this complex beverage. The interplay between hops, malt, and other ingredients creates a diverse range of flavours and aromas, ensuring there's a beer to suit every taste.

Exploring the Diverse World of Michelob Beers

You may want to see also

Acidity: the tangy quality, similar to the tartness in wines

Acidity is a term referring to sour, tangy or tart flavours derived from organic acids. It is the state of being acid, or the extent to which a solution is acid. Acidity relates to the sharpness of the taste of beer.

Beer is slightly acidic, with an average pH of 4.0-4.4. The pH scale ranges from 0 to 14, with 7 being the neutral value, which is usually the value of pure water. Solutions with a pH under 7 are considered acidic, and those with a pH over 7 are considered alkaline. Beer is more acidic than coffee, milk, and water, but less acidic than wine.

The perception of sourness or tartness is caused by hydrogen ions (H+) of an organic acid on the tongue's flavour receptors. In beer, the organic acids that play a role in flavour are acetic, lactic, citric, and malic. The two acids that are most directly related are lactic and acetic.

Acidity is detected via taste and can be determined by titration against a standard base. When beer is analysed in a laboratory, the acidity is expressed as if all the acidity were present as lactic acid, for convenience. The total concentration of acidity is described in the literature as 220-500 parts per million (ppm), adding to the pleasing tartness of beer. However, measurements of 0.1% to 0.3% acidity (expressed as lactic) are typical in beer, which would calculate to 1000 to 3000 ppm.

Measuring pH is critical in many steps of beer making, such as adjusting mash pH for optimal enzyme activity, or acidifying the brew kettle before fermentation. Final fermentation pH can also indicate yeast health or cellaring techniques.

Titratable Acidity (TA) is a useful measurement for brewers to understand how much of a particular acid (most often lactic acid) is in a beer. TA measures the total amount of hydrogen ions or acidic compounds tied up in other bonds. By titrating a sour beer, a brewer can determine the amount of acid in the solution. TA is measured in grams per litre and measures the ability of an acid to neutralise an alkaline or basic liquid.

TA has been used in winemaking for decades, and some brewers are now starting to use it to set and reach targets for their beers. It is a better indicator of the experiential sourness of beer than pH, as we taste acids, not pH. It is also easy to find two beers with the same pH but different levels of perceived sourness.

Acidity can be balanced in beer by characteristics like sweetness, bitterness, fruit character, alcohol, and carbonation. The balance of a beer is determined by its overall character.

Beer Carbonation: Why the Fizz Differs

You may want to see also

Roastiness: a strong flavour from dark, roasted malts, with coffee-like, chocolatey, or smoky notes

Roastiness is a flavour derived from roasted malts, which are malts that have been roasted at very high temperatures, generally above 400°F (200°C). This is in contrast to kilning them at low to moderate temperatures. Roasted malts are the darkest malts available to a brewer, with colours ranging from around 200 L to 600 L or more.

Roasted malts are used to create unique colours, flavours, and aromas through intense Maillard reactions—the chemical reaction of amino acids and reducing sugars, and/or caramelisation of sugars at high temperatures. The high temperatures applied during roasting completely deactivate all enzymes developed during malting.

There are two distinctive categories of roasted malts: roasted "green" malts (caramel malts) and dry roasted malts (brown, chocolate, and black malts). Caramel malts are produced by bypassing the kiln and introducing germinated barley (green malt) directly into a roaster at a relatively high moisture content. Dry roasted malts, on the other hand, are produced by roasting kiln-dried malt at low moisture and very high temperatures.

The flavours and aromas of roasted malts can include coffee, mocha, burnt toast, roasted flavours, bittersweet, tannic (like sucking on a tea bag), and dry acrid flavours. Black malt, also known as "black patent" or "patent malt", is so highly roasted that many flavour and aroma compounds are volatilised off, leaving only dark roasted, coffee-like, slightly astringent flavours.

Roasted malts are primarily used in darker beer styles such as English and American browns, porters, stouts, black IPAs, and continental dark beers like Bock. They can also be used in small amounts in lighter beers to add colour without significantly changing the flavour.

EBC Beer Shipping: State-by-State Availability and Restrictions

You may want to see also

Hoppiness: the aromatic and bitter qualities of hops added during fermentation

The addition of hops during fermentation is a critical factor in determining the flavour profile of beer, specifically its hoppiness—the aromatic and bitter qualities derived from hops. Hops contribute to the intensity of bitterness, as well as fruity, herbal, or spicy flavours in the final beer. The timing of hop additions during fermentation, particularly during the boiling process, plays a significant role in the resulting flavour and aroma.

Timing of Hop Additions

The boiling process can cause a loss of hop oils, which are responsible for flavour and aroma. The longer the boil time, the more oils are lost. Hops added at the beginning of the boil primarily contribute to bitterness due to the release of alpha acids, which undergo isomerization when heated. This process imparts a more bitter taste to the beer. Conversely, hops added towards the end of the boil retain more of their oils, resulting in a more delicate bitterness and subtle flavours and aromas.

Dry Hopping

Dry hopping is a technique where hops are added to the beer after fermentation has begun, or even after it has finished. This method preserves the delicate volatile oils in the hops, enhancing the beer's aroma without adding bitterness. The optimal time for dry hopping is just as fermentation starts to slow down, usually three to four days after it has begun. This timing ensures the survival of the desired hop aromas and flavours while minimising the risk of contamination from hops, which are not a sterile product.

Biotransformation

Biotransformation is a chemical process that occurs during dry hopping, particularly when hops are added during active primary fermentation. This process involves the interaction of yeast and hops, enhancing the flavours and aromas of the final product. Certain strains of yeast can alter and liberate some flavour compounds in hop oils, leading to unique flavour profiles. For example, the transformation of geraniol to β-citronellol is often cited by brewers.

Factors Affecting Hop Aroma and Flavour

The type of hops used, such as pellets or whole hops, can impact the release of hop oils and, consequently, the aroma and flavour of the beer. Pellets initially float but eventually settle, while whole hops tend to float on the surface. Pellets have ruptured lupulin glands, allowing hop oils to be released into the beer more quickly, usually within a few days. Whole hops, on the other hand, have intact lupulin glands, resulting in a slower release of hop oils, which may take up to a week or two.

The amount of hops used during dry hopping also affects the intensity of the hop aroma and flavour. Generally, using more hops will result in a hoppier beer. However, the specific variety of hops and their oil content also play a role. Some hops have a more potent or distinctive aroma, allowing them to stand out even with lower oil levels. For example, Cascade hops are known for their high oil levels and distinctive citrusy aroma.

Temperature is another factor that influences the quality and strength of the hop aroma. Warmer temperatures tend to extract more oils, particularly from whole hops. A general guideline is to dry hop at temperatures around 70 °F (21 °C).

Hop-Forward Beer Styles

Beer styles that prominently feature hops and emphasise their aromatic and bitter qualities include:

- India Pale Ales (IPAs): This style includes a wide range of variations, such as West Coast IPA, British IPA, and New England Style IPA, each with distinct flavour profiles. IPAs are known for their strong presence of hops, often resulting in herbal, citrus, or fruity flavours.

- Pale Ales: While typically having a lower alcohol content than IPAs, pale ales can still be hoppy and feature a variety of styles, such as American amber ale, American pale ale, blonde ale, and English pale ale.

- American Imperial IPA: This style is characterised by a bold, herbal, and citric flavour profile due to the heavy use of intensely flavoured hops.

- Pilsners: Originating from the Czech Republic, pilsners can be either German pilsners, which are pale gold and crisp, or Czech pilsners, which are slightly darker and more bitter.

Exploring Diverse Beer Markets: A Global Perspective

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Off-flavours in beer can be caused by contamination, poor brewing practices, or poor beer handling. Some common off-flavours include diacetyl (buttery or butterscotch), mercaptan (rotten vegetables or garbage), and lightstruck (skunky).

The basic flavours of beer include sweetness, bitterness, acidity, roastiness, and hoppiness. Sweetness comes from the residual sugars left in the brew after fermentation, while bitterness comes from hops. Acidity in beer is similar to the tartness found in wines, and can be influenced by the presence of acids such as lactic acid or acetic acid. Roastiness comes from dark, roasted malts, and gives the beer a strong flavour, often with coffee-like, chocolatey, or smoky notes. Hoppy beers have bitterness as well as other flavour characteristics, such as floral, fruity, piney, or earthy notes.

Common flavour notes in different types of beer include:

- Stouts: coffee, chocolate, cream, espresso

- Porters: chocolate

- IPAs: hops, herbs, citrus, or fruity flavours

- Pale ales: malty, medium-bodied

- Pilsners: crisp flavour, pale gold colour (German pilsners); darker colour, higher bitterness (Czech pilsners)

- Wheat beers: light, tangy, funky, bread-like

- Sour beers: sweet and sour, with added fruits like cherry, raspberry, or peach