Beer is one of the world's most beloved beverages, and its history is as old as civilization itself. In this episode of Stuff You Should Know, Josh and Chuck delve into the fascinating world of beer, exploring its rich history, intricate brewing process, and cultural significance. From ancient Sumerians to modern craft breweries, beer has played a pivotal role in shaping societies and bringing people together.

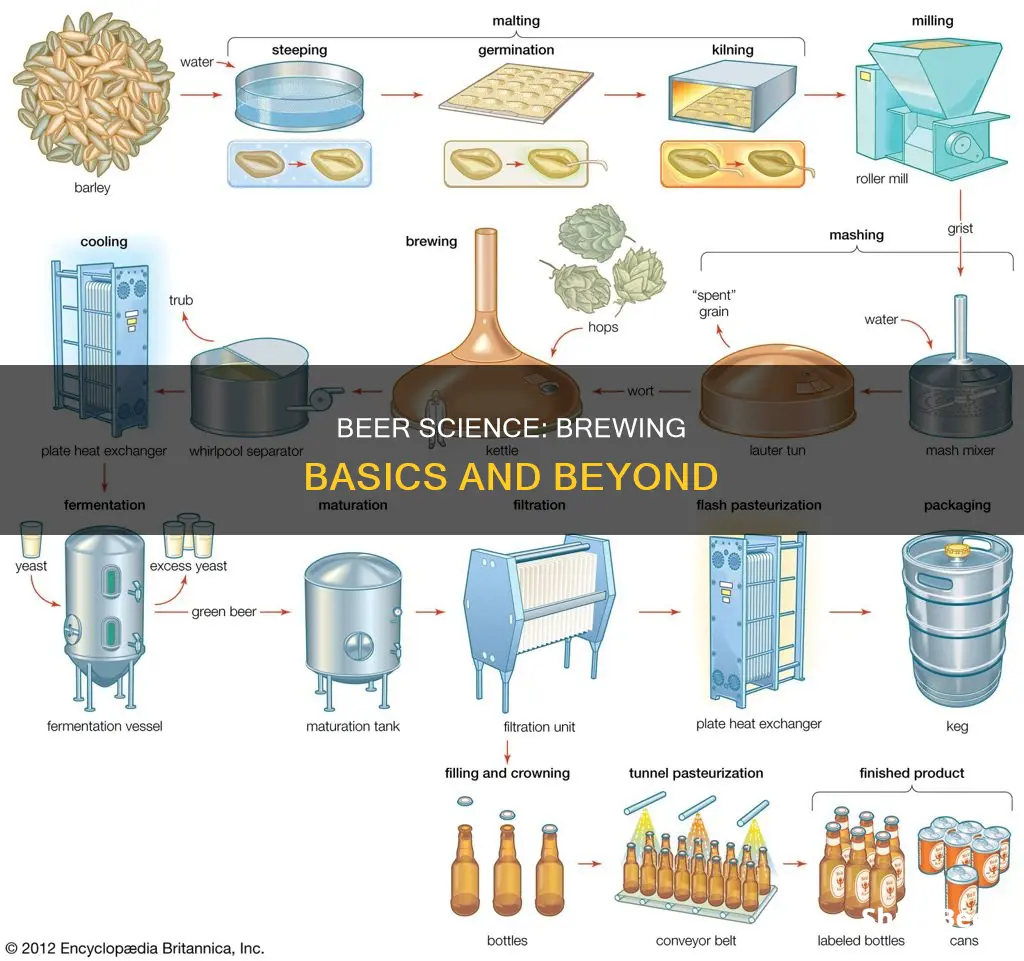

Throughout the episode, Josh and Chuck unravel the complex art of beer-making, shedding light on the key ingredients and biochemical reactions that transform barley into fermentable sugars and eventually, delicious beer. They discuss the importance of yeast, hops, water, and grain, and how variations in these ingredients create distinct styles like ales and lagers. The hosts also touch on the impact of historical events, such as Prohibition and World War II, which influenced the types of beer we drink today.

With a perfect blend of humour and insight, Josh and Chuck guide listeners through the ins and outs of beer, offering a deeper appreciation for this beloved beverage. So grab a cold one, sit back, and get ready to explore the wonderful world of beer!

What You'll Learn

The four main ingredients of beer

Water

The most abundant ingredient in beer is water, which makes up the majority of its volume. The type of water used in brewing can significantly impact the flavour and quality of the final product. Brewers usually prefer filtered water, which strikes a balance between purity and mineral content. The mineral concentration in water can affect the taste of beer—beers brewed with hard water tend to have a fuller body and more bitterness than those made with soft water.

Grains

Grains, typically malted barley, are another essential component of beer. The starches in grains are converted into sugars during the brewing process, which then interact with yeast to produce alcohol through fermentation. The colour of the grains influences the hue of the beer, with darker grains yielding darker beers. Grains also affect the viscosity and mouthfeel of the drink, as well as the thickness of the beer head.

Hops

Hops, the flowers of the Humulus lupulus plant, are responsible for the bitterness, aroma, and flavour of beer. They contain essential oils and resins that contribute to the characteristic bitterness and pleasant floral aroma of beer. Hops are added during the boiling process and play a crucial role in stabilising the beer and extending its shelf life by exerting an antibacterial effect.

Yeast

Yeast is a key ingredient in beer, responsible for the fermentation process that gives beer its unique flavour and aroma. It is a microscopic single-celled organism that feeds on the sugars present in the grains, converting them into alcohol and carbon dioxide. There are two main types of yeast used in brewing: ale yeast, which ferments at higher temperatures and produces a sweeter, fruitier flavour; and lager yeast, which ferments at lower temperatures, resulting in a crisper, cleaner flavour.

Beer Aids: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

The process of fermentation

Fermentation is the process by which yeast converts the glucose in the wort to ethyl alcohol and carbon dioxide gas, giving the beer its alcohol content and carbonation. Brewers combine barley, water, hops, and yeast to make beer. However, it's not just a matter of mixing the ingredients and letting them settle. A complex series of biochemical reactions must take place to convert barley to fermentable sugars, and to allow yeast to live and multiply, converting those sugars to alcohol.

To begin the fermentation process, the cooled wort is transferred into a fermentation vessel to which the yeast has already been added. The specific gravity of the mixture is measured at the beginning, and later, it may be measured again to determine the alcohol content and know when to stop the fermentation. The fermenter is sealed off from the air except for a long, narrow vent pipe, which allows carbon dioxide to escape from the fermenter. This constant flow of CO2 prevents outside air from entering the fermenter, reducing the threat of contamination by stray yeasts.

Fermentation produces a substantial amount of heat, so the tanks must be constantly cooled to maintain the proper temperature. The temperature is critical in controlling the outcome of fermentation and has a significant impact on the development of flavor. Ales are generally fermented at a temperature between 16°C and 22°C, using top-fermenting yeast strains, whereas lagers are fermented much cooler, at 9°C–14°C, using bottom-fermenting strains.

When fermentation is nearly complete, most of the yeast will settle at the bottom of the cone-shaped fermenter, making it easy to capture and remove the yeast for reuse in the next batch. The yeast can be reused several times before it needs to be replaced, usually when it has mutated and produces a different taste. Commercial brewing is all about consistency, so this is an important step.

While fermentation is still happening, and when the specific gravity has reached a predetermined level, the carbon dioxide vent tube is capped. Now the vessel is sealed, so as fermentation continues, pressure builds as CO2 continues to be produced. This is how the beer gets most of its carbonation, and the rest will be added manually later. From this point on, the beer will remain under pressure (except for a short time during bottling).

When fermentation is finished, the beer is cooled to about 32°F, helping the remaining yeast and other undesirable proteins to settle at the bottom of the fermenter. Now that most of the solids have settled, the beer is slowly pumped from the fermenter and filtered to remove any remaining solids. From the filter, the beer goes into another tank, called a bright beer tank. This is its last stop before bottling or kegging. Here, the level of carbon dioxide is adjusted by bubbling a little extra CO2 into the beer through a porous stone.

Beer Goggles: The Science Behind Alcohol's Effect on Attraction

You may want to see also

Beer's history

Beer is one of the oldest human-produced drinks, with the earliest archaeological evidence of fermentation dating back 13,000 years. Beer was likely discovered by accident, when a pile of grain sat out in the rain and sun, and wild yeast latched onto its sugar. The earliest written records of brewing come from Mesopotamia (ancient Iraq). These include early evidence of beer in a 3,900-year-old Sumerian poem honouring Ninkasi, the patron goddess of brewing, which contains the oldest surviving beer recipe. Beer was also mentioned in the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which the 'wild man' Enkidu is given beer to drink.

Beer was produced on a domestic scale in Neolithic Europe as far back as 5,000 years ago. In ancient Rome, beer was replaced in popularity by wine, and Tacitus wrote disparagingly of the beer brewed by the Germanic peoples of his day. In the Middle Ages, beer was consumed daily by all social classes in the northern and eastern parts of Europe, and brewing was considered a common household task, orchestrated by women. In the 1400s in Germany, a type of beer was made that was fermented in the winter with a different type of yeast. This beer was called a lager, and, in part due to Prohibition, a variation of this type of beer is dominant in the United States today.

In the 16th century, William IV, Duke of Bavaria, adopted the Reinheitsgebot (purity law), perhaps the oldest food regulation still in use through the 20th century. The Gebot ordered that the ingredients of beer be restricted to water, barley, and hops; yeast was added to the list after Louis Pasteur's discovery in 1857.

In the United States, the production of beer was banned for 13 years starting in 1920, forcing most breweries out of business. By the time the laws were repealed in 1933, only the largest breweries had survived. During World War II, with food in short supply and many men overseas, breweries started brewing a lighter style of beer that is very common today. Since the early 1990s, small regional breweries have made a comeback, popping up all over the United States, and variety has increased.

Beer, Anxiety, and You: A Curious Concoction

You may want to see also

Beer and water sanitation

The Importance of Sanitation

Sanitation is paramount in brewing delicious beer. Contamination from wild yeast or bacteria can lead to off-flavors and undesirable aromas. By maintaining proper sanitation, brewers can prevent their wort and beer from being infected by unwanted microorganisms. This involves a two-step process: cleaning and then sanitizing.

Cleaning

The first step is cleaning, which involves removing dirt, dried beer, wort, and other residues from equipment. This step ensures that bacteria have nowhere to hide and creates a smooth surface for sanitizers to work effectively. Cleansers such as Powdered Brewery Wash (PBW) or OxiClean Free are commonly used for this purpose.

Sanitizing

The second step is sanitizing, which involves killing any remaining bacteria and microorganisms. Popular sanitizing agents include Star-San, Iodophor, and B-brite. It's important to sanitize anything that comes into contact with the wort or beer after boiling, including fermentation vessels, spoons, hydrometers, tubing, and bottles.

Water Sanitation

Water sanitation is also crucial, as the alcohol content in beer is not sufficient to kill all bacteria. In the Middle Ages, beer provided a safer alternative to water due to the sanitizing effects of alcohol. However, today's beer typically has a lower alcohol content, so proper water sanitation is essential to prevent contamination.

Beer Traps: Effective Snail Control or Urban Myth?

You may want to see also

Beer and food pairing

Contrast is when a beer or dish has one strong, dominant flavour, such as sweet, rich, or oily. An example is oysters and stout, where the strong, briny flavour of the oysters can stand up to the rich texture and chocolatey notes of the stout. Complementing flavours is another simple way to make a delicious pairing. Match rich foods with heavy and rich-flavoured beers, like stouts or porters, or pair light-tasting salads and fish with light beers or wheat beers.

Beer can also serve as a palate cleanser, which works well with dishes that have bold or intense flavours, such as spicy Indian cuisine or rich fried foods. A light beer can be used to wash down the heat of spicy food, and fatty foods can help balance out the bitterness of an IPA. It is important to avoid overpowering flavours, as some medium and dark beers can have rich and powerful flavours that can overwhelm certain types of food. For example, the flavour of a pint of Guinness would completely cover the taste of salmon.

There are also specific pairings that work for different types of beer. Light lagers, for example, are very refreshing and can be paired with spicy dishes, burgers, or salads. Wheat beers are versatile and can be paired with many foods, including spicy food and fruity desserts. India pale ales (IPAs) work well with steak, barbecue, and Mexican food. Amber ales go well with pizza, fried food, and smoked pork, while dark lagers complement pizza, burgers, and hearty stews. Brown ales are famous for pairing well with almost anything but are particularly good with the rich chocolate and nutty flavours of certain dishes. Porters are best paired with foods that have similar taste and texture, such as game meats, seafood, and coffee-flavoured desserts. Finally, stouts are perfect for pairing with chocolate desserts and shellfish, as well as Mexican food.

Mouthwash and Beer: Effective Mosquito Repellents or Old Wives' Tales?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The four main ingredients of beer are grain (usually malted barley), hops, yeast, and water.

Ales and lagers are categories of beer, not styles. The difference comes down to the type of yeast used during fermentation and the temperature at which it takes place. Ale yeast ferments at warmer temperatures and produces brighter, fruitier, and spicier flavors. Lager yeast ferments at cooler temperatures and results in a smoother finish.

The brewing process involves several steps, including mashing, lautering, sparging, and boiling. During mashing, the starches in malted barley are converted into fermentable sugars. The grains are crushed and mixed with heated water to break down the starches into simpler sugars. The liquid is then drained and recirculated, and additional water is poured over the grains (sparging) to ensure all sugars are extracted. Finally, the liquid is boiled, and hops are added for bitterness, flavor, and aroma.